The

story of America's first modern

political campaign seems almost

too absurd to be true; it would

tax a fertile imagination to

weave Daniel Webster, Simon

Bolivar, the Shawnee leader

Tecumseh and a sitting president

with the improbable nickname

"Sweet Sandy Whiskers" into a

believable tale.

The

story of America's first modern

political campaign seems almost

too absurd to be true; it would

tax a fertile imagination to

weave Daniel Webster, Simon

Bolivar, the Shawnee leader

Tecumseh and a sitting president

with the improbable nickname

"Sweet Sandy Whiskers" into a

believable tale.

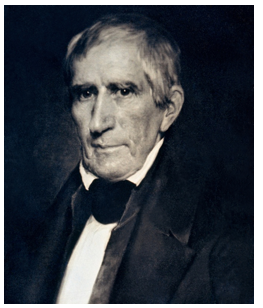

The man at the center of the

madness, William Henry Harrison

(1773 - 1841), was born into a

wealthy and aristocratic Virginia

family. After a brief stint

in medical school, Harrison found

his footing in the military, a

guaranteed path to adventure as

the young country was continually

embroiled in battle in some

corner or another.

medical school, Harrison found

his footing in the military, a

guaranteed path to adventure as

the young country was continually

embroiled in battle in some

corner or another.

Valor and family

connections landed Harrison

governorship of the Indiana

Territory, where for 12 years he

aggressively negotiated land

purchases with Native Americans,

including the Treaty of Fort

Wayne, a land grab of over three

million acres in 1809. The

Shawnee leader Tecumseh

vehemently denied the legitimacy

of the treaty and organized a

confederacy of tribes to oppose

the settlers.

In November 1811, Harrison led a

group of nearly 1,000 men toward

the Tippecanoe River in the

north. He eventually beat back

the tribes, but lost several

dozen men in the fight. He would

enjoy greater success later in

the War of 1812, but it was the

battle at Tippecanoe that stuck

with Harrison.

The next years

brought ... not much. In fact

Harrison spent the next two

decades unremarkably, variously

serving in Congress and hitting

up friends  for

appointments he thought might

advance his career. Most notably

he was dispatched by President

John Quincy Adams to serve as an

envoy to Columbia; he stayed in

Bogota long enough to announce

his disapproval of President

Simon Bolivar, blatantly

disregarding an order from the

White House to keep his nose out

of local politics. Harrison was

yanked back to America when the

Andrew Jackson administration

came to power, and he

subsequently settled in to

semi-retirement at his farm in

Ohio. He re-emerged on the

national scene in 1836 as part of

the Whig Party's ill-conceived

multi-candidate ticket created to

oppose Democrat Martin Van Buren,

who would become president.

for

appointments he thought might

advance his career. Most notably

he was dispatched by President

John Quincy Adams to serve as an

envoy to Columbia; he stayed in

Bogota long enough to announce

his disapproval of President

Simon Bolivar, blatantly

disregarding an order from the

White House to keep his nose out

of local politics. Harrison was

yanked back to America when the

Andrew Jackson administration

came to power, and he

subsequently settled in to

semi-retirement at his farm in

Ohio. He re-emerged on the

national scene in 1836 as part of

the Whig Party's ill-conceived

multi-candidate ticket created to

oppose Democrat Martin Van Buren,

who would become president.

In

1840 the Whigs saw a window of

opportunity to dislodge the

Democrats. That window presented

itself in the form of

catastrophic financial collapse:

inflation and unemployment

soared, businesses were lost and

crop prices plummeted. Van Buren

did little to endear himself to a

frightened nation: he blamed the

crisis on unscrupulous bankers

and greedy Americans, and

maintained that the government

should not interfere with private

business.

In

1840 the Whigs saw a window of

opportunity to dislodge the

Democrats. That window presented

itself in the form of

catastrophic financial collapse:

inflation and unemployment

soared, businesses were lost and

crop prices plummeted. Van Buren

did little to endear himself to a

frightened nation: he blamed the

crisis on unscrupulous bankers

and greedy Americans, and

maintained that the government

should not interfere with private

business.

Of the losing Whig

candidates back in 1836, Harrison

was most successful, so he was

chosen to oppose Van Buren. The

Democrats must have been elated:

Harrison was old - older by 20

years than Van Buren. And he

hadn't really been involved in

the Washington political scene

for years. Even with the

financial crisis it probably

seemed like Van Buren could

secure a second term.

The law of unintended

consequences played out shortly

thereafter when a Democratic

newspaper in Baltimore openly

dismissed Harrison's  candidacy,

implying he was a simpleton,

ready to be put out to

pasture:

candidacy,

implying he was a simpleton,

ready to be put out to

pasture:

"Give him a barrel of

hard cider, and settle a pension

of $2,000 on him, and our word

for it, he will sit the remainder

of his days in his log cabin by

the side of the sea-coal fire and

study moral philosophy."

The image of

Harrison as a log cabin-dwelling

"everyman," enjoying a good cider

and a warm fire, was exactly what

the Whigs needed to energize the

masses. Hedging their bets, Van

Buren was portrayed as a

blue-blooded dandy, aloof and

unresponsive to the concerns of

the common man. In reality he was

born to a humble Dutch farming

family and left school at age

14.

The beginning of the end for Van

Buren was the "Gold Spoon

Oration" of Whig Congressman

Charles Ogle of Pennsylvania.

Ogle ostensibly took the House

floor to address a request for

funds to renovate the White

House, but instead delivered a

3-day skewering of the President,

excoriating him for what Ogle

described as an extravagant

lifestyle.

Ogle

told his colleagues and

spectators that "Sweet Sandy

Whiskers" (the derisive Whig

nickname for Van Buren) ate his

dinners at a table arrayed with

gold utensils, and dipped his

"pretty, tapering, soft, white,

lily fingers" in fancy finger

cups paid for with the "People's

cash." Of course there weren't

gold forks or spoons in the White

House, and Van Buren actually

spent very little public money

during his term, but the

characterization of him as an

elitist had already taken

hold.

Ogle

told his colleagues and

spectators that "Sweet Sandy

Whiskers" (the derisive Whig

nickname for Van Buren) ate his

dinners at a table arrayed with

gold utensils, and dipped his

"pretty, tapering, soft, white,

lily fingers" in fancy finger

cups paid for with the "People's

cash." Of course there weren't

gold forks or spoons in the White

House, and Van Buren actually

spent very little public money

during his term, but the

characterization of him as an

elitist had already taken

hold.

Harrison on the

other hand was now the "log cabin

and hard cider" candidate, a war

hero who would inhabit the office

of the Presidency as a dutiful

proxy of the average man. Ohio

distillery E.C. Booz produced log

cabin-shaped whiskey bottles,

passed out at massive rallies

where bands played songs from The

Log Cabin Songbook, with lyrics

that reinforced the manufactured

personas:

Let Van from his

coolers of silver drink wine,

And lounge on his cushioned

settee,

Our man on a buckeye bench can

recline,

Content with hard cider is

he.

Cups, plates,

posters and flags were printed

with Harrison's face. A newspaper

called the Log Cabin covered

campaign events, printed speeches

and songs, and sold thousands of

copies each week. The Whigs

promoted their ticket with the

slogan and song "Tippecanoe and

Tyler Too" - "Tippecanoe" of

course referred to Harrison's

military victory, and "Tyler" was

his running mate, John Tyler.

On the pesky matter

of "issues" Harrison adhered to

the advice of the Whigs and kept

quiet - so much so that the

Democrats dubbed him "General

Mum."

It was an incredibly well planned

operation designed to please the

crowds, and it worked. Van Buren

for the most part ran a

traditional campaign, preferring

to concentrate on policy matters.

Toward the end, though, the

Democrats tried to counter-attack

with songs of their own:

Rockabye, baby, when

you awake

You will discover Tip is a

fake.

Far from the battle, war cry and

drum

He sits in his cabin a'drinking

bad rum.

But it was too

later. Over 80 percent of the

eligible population took to the

polls that November, and Harrison

won both the popular and the

electoral vote - the electoral by

a margin of 234 to 60.

Eager to prove he

wasn't the rube of campaign lore,

Harrison crafted a colossal

commencement speech, shoehorning

classical allusions

throughout. He let his friend and new

Secretary of State Daniel Webster

take a pass at editing it; though

Webster slashed through,

remarking he killed "seventeen

Roman proconsuls as dead as

smelts, every one of them," it

still stands as the longest

inaugural address of any

president. Harrison stood for an

hour and a half in the rainy cold

detailing the Whig agenda and

vowing, "Under no circumstances

will I consent to serve a second

term."

He let his friend and new

Secretary of State Daniel Webster

take a pass at editing it; though

Webster slashed through,

remarking he killed "seventeen

Roman proconsuls as dead as

smelts, every one of them," it

still stands as the longest

inaugural address of any

president. Harrison stood for an

hour and a half in the rainy cold

detailing the Whig agenda and

vowing, "Under no circumstances

will I consent to serve a second

term."

Fate took that

decision out of his hands -

Harrison caught pneumonia and

died a month later. "His

Accidency," as Democrats dubbed

Tyler, took the oath and

proceeded to veto nearly every

Whig bill that crossed his desk;

his cabinet resigned in disgust

and the Whigs never truly

recovered.

Sources:

Bartleby.Com.

William

Henry Harrison. Inaugural

Address. Thursday, March 4,

1841.

Bryant, William Cullen.

Power

For Sanity: Selected Editorials

of William Cullen Bryant,

1829-1861. Fordham

University Press, 1994.

EDSITEment, National Endowment

for the Humanities. The

Campaign of 1840: William Henry

Harrison and Tyler,

Too.

Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 25,

2009, from William

Henry Harrison. (2009).

HistoryNet. American

History: 1840 U.S. Presidential

Campaign.

Kingsbury, Alex. "William

Henry Harrison, Martin Van Buren,

and the Birth of the Modern

Political Campaign". U.S.

News & World Report,

January 17, 2008.

The Miller Center for Public

Affairs, University of

Virginia. William

Henry

Harrison.

Remini, Robert Vincent. Daniel

Webster: the man and his

time. New York: W.W.

Norton & Company 1997.

Tarbell, Ida M. "Abraham

Lincoln." McClure's

Magazine, Volume VI, April

1896, No. 5

Tippecanoe County Historical

Association. Tippecanoe

Battlefield

History.

Van Meter, Jan R. Tippecanoe

and Tyler Too: Famous Slogans and

Catchphrases in American

History. University Of

Chicago Press, 2008.

The White House. William

Henry Harrison.